Buried within the archives of a museum in Missouri, an essay on the search for alien life has come to light, 78 years after it was penned. Written on the brink of the second world war, its unlikely author is the political leader Winston Churchill.

If the British prime minister was seeking solace in the prospect of life beyond our war-torn planet, would the discovery of a plethora of exoplanets aid or hinder such comfort?

The 11-page article – Are We Alone in the Universe? – has sat in the US National Churchill Museum archives in Fulton, Missouri from the 1980s until it was reviewed by astrophysicist Mario Livio in this week’s edition of the journal Nature.

Livio highlights that the unpublished text shows Churchill’s arguments were extremely contemporary for a piece written nearly eight decades previously. In it, Churchill speculates on the conditions needed to support life but notes the difficulty in finding evidence due to the vast distances between the stars.

Churchill fought the darkness of wartime with his trademark inspirational speeches and championing of science. This latter passion led to the development of radar, which proved instrumental to victory over Nazi Germany, and a boom in scientific advancement in post-war Britain.

Churchill’s writings on science reveal him to be a visionary. Publishing a piece entitled Fifty Years Hence in 1931, he detailed future technologies from the atomic bomb and wireless communications to genetic engineered food and even humans. But as his country faced the uncertainty of another world war, Churchill’s thoughts turned to the possibility of life on other worlds.

In the shadow of war

Churchill was not alone in contemplating alien life as war ripped across the globe.

Just before he wrote his first draft in 1939, a radio adaption of HG Wells’ 1898 novel War of the Worlds was broadcast in the US. Newspapers reported nationwide panic at the realistic depiction of a Martian invasion, although in truth the number of people fooled was probably far smaller.

The British government was also taking the prospect of extraterrestrial encounters seriously, receiving weekly ministerial briefings on UFO sightings in the years following the war. Concern that mass hysteria would result from any hint of alien contact resulted in Churchill forbidding an unexplained wartime encounter with an RAF bomber from being reported.

Faced with the prospect of widespread destruction during a global war, the raised interest in life beyond Earth could be interpreted as being driven by hope.

Discovery of an advanced civilisation might imply the huge ideological differences revealed in wartime could be surmounted. If life was common, could we one day spread through the Galaxy rather than fight for a single planet? Perhaps if nothing else, an abundance of life would mean nothing we did on Earth would affect the path of creation.

Churchill himself appeared to subscribe to the last of these, writing:

I, for one, am not so immensely impressed by the success we are making of our civilisation here that I am prepared to think we are the only spot in this immense universe which contains living, thinking creatures.

A profusion of new worlds

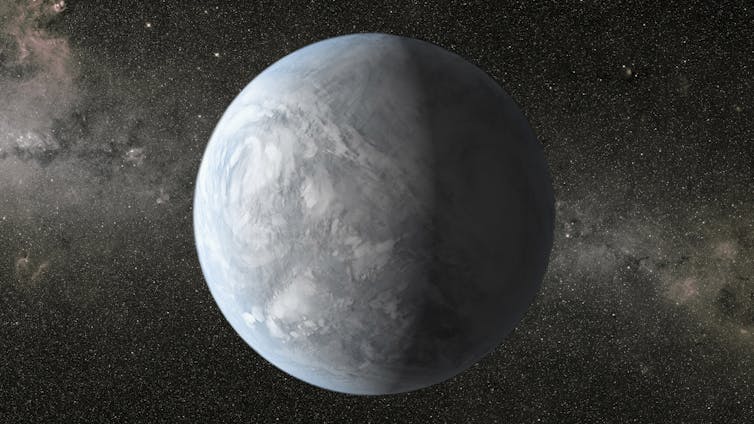

Were Churchill prime minister now, he might find himself facing a similar era of political and economic uncertainty. Yet in the 78 years since he first penned his essay, we have gone from knowing of no planets outside our Solar System to the discovery of around 3,500 worlds orbiting around other stars.

Had Churchill lifted his pen now – or rather, touched his stylus to his iPad Pro – he would have known planets could form around nearly every star in the sky.

This profusion of new worlds might have heartened Churchill and many parts of his essay remain relevant to modern planetary science. He noted the importance of water as a medium for developing life and that the Earth’s distance from the Sun allowed a surface temperature capable of maintaining water as a liquid.

He even appears to have touched on the fact that a planet’s gravity would determine its atmosphere, a point frequently missed when considering how Earth-like a new planet discovery may be.

To this, a modern-day Churchill could have added the importance of identifying biosignatures; observable changes in a planet’s atmosphere or reflected light that may indicate the influence of a biological organism. The next generation of telescopes aim to collect data for such a detection.

By observing starlight passing through a planet’s atmosphere, the composition of gases can be determined from a fingerprint of missing wavelengths that have been absorbed by the different molecules. Direct imaging of a planet may also reveal seasonal shifts in the reflected light as plant life blooms and dies on the surface.

Where is everybody?

But Churchill’s thoughts may have taken a darker turn in wondering why there was no sign of intelligent life in a Universe packed with planets. The question “Where is everybody?” was posed in a casual lunchtime conversation by Enrico Fermi and went on to become known as the Fermi Paradox.

The solutions proposed take the form of a great filter or bottleneck that life finds very difficult to struggle past. The question then becomes whether the filter is behind us and we have already survived it, or if it lies ahead to stop us spreading beyond planet Earth.

Filters in our past could include a so-called “emergence bottleneck” that proposes that life is very difficult to kick-start. Many organic molecules such as amino acids and nucleobases seem amply able to form and be delivered to terrestrial planets within meteorites. But the progression from this to more complex molecules may require very exact conditions that are rare in the Universe.

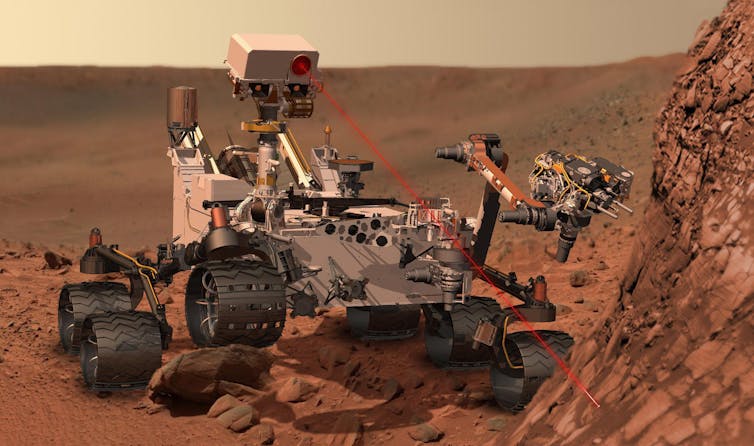

The continuing interest in finding evidence for life on Mars is linked to this quandary. Should we find a separate genesis of life in the Solar System – even one that fizzled out – it would suggest the emergence bottleneck didn’t exist.

It could also be that life is needed to maintain habitable conditions on a planet. The “Gaian bottleneck” proposes that life needs to evolve rapidly enough to regulate the planet’s atmosphere and stabilise conditions needed for liquid water. Life that develops too slowly will end up going extinct on a dying world.

A third option is that life develops relatively easily, but evolution rarely results in the rationality required for human-level intelligence.

The existence of any of those early filters is at least not evidence that the human race cannot prosper. But it could be that the filter for an advanced civilisation lies ahead of us.

In this bleak picture, many planets have developed intelligent life that inevitably annihilates itself before gaining the ability to spread between star systems. Should Churchill have considered this on the eve of the second world war, he may well have considered it a probable explanation for the Fermi Paradox.

Churchill’s name went down in history as the iconic leader who took Britain successfully through the second world war. At the heart of his policies was an environment that allowed science to flourish. Without a similar attitude in today’s politics, we may find we hit a bottleneck for life that leaves a Universe without a single human soul to enjoy it.